Ed Eiteljorg had just turned one year old when his family disembarked from their ship Main at Ellis Island in 1872. Soon after landing in the United States, the family settled in Indiana where Eiteljorg learned the ways of America, including the national pastime of baseball.

Ed Eiteljorg had just turned one year old when his family disembarked from their ship Main at Ellis Island in 1872. Soon after landing in the United States, the family settled in Indiana where Eiteljorg learned the ways of America, including the national pastime of baseball.

Born on October 14, 1871 in Berlin, Germany to Carl Heinrich and Augusta (Baisenberg) Eiteljorg, Edward Henry was the third of four sons born to the farmer and his wife. The fourth was born in Greencastle, Indiana – the home the Eiteljorg’s would make their own not long after coming to America. Carl took up shoemaking in Greencastle and his children all appear to have finished high school, save for one. Albert became a dentist in Indianapolis and Charles was a successful businessman. The youngest son, Henry, died as a toddler in 1880.

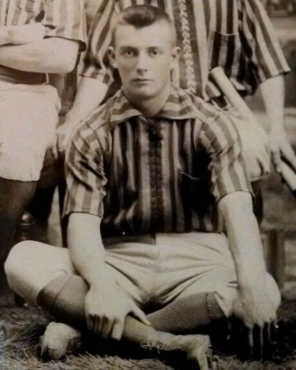

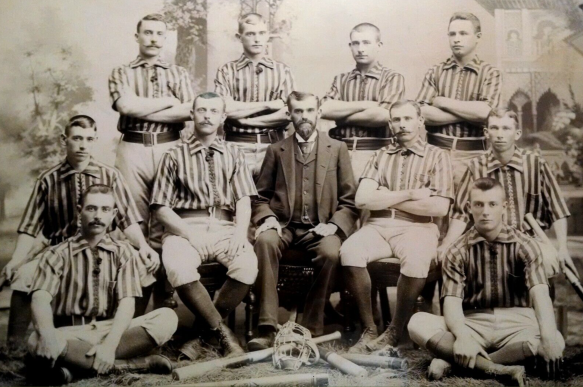

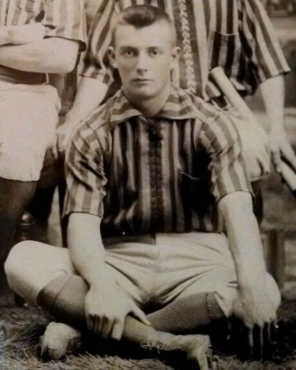

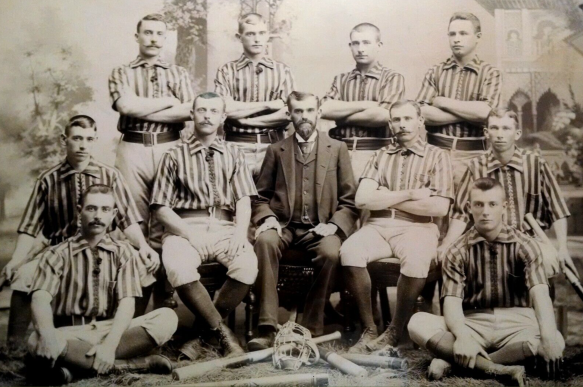

After high school, Eiteljorg enrolled at Depauw University and was a student there when he began pitching for Terre Haute in the Interstate League for 1889. This team won 20 of 25 games – and one paper said his name alone was intimidating. “Terre Haute has a pitcher named Eiteljorg. Printed in big letters on the scoreboard, it alone gives rival teams the horrors.” In the photo of the 1889 Terre Haute team below, Ed is seated at the lower right. Joe Cantillon, years before his greater fame, sits behind Eiteljorg’s right shoulder.

At the end of the season, Eiteljorg earned a tryout with Indianapolis, where he would sign a contract for 1890. He defeated both Kansas City and Columbus in exhibition games. After beating Kansas City, an Indianapolis reporter wrote, “He is only eighteen years of age, but he pitched like a veteran, and after he had finished the game he could have put his name to a contract with either Manager (Jack) Glasscock or Watkins.” However, Indianapolis chose to close up shop as 1890 began, selling off player rights and other assets. The Chicago Colts purchased the rights to Eiteljorg and brought him to Hot Springs, Arkansas for spring training.

“He is a big, strapping fellow and comes with a great reputation secured with several good semi-professional teams… He is big and heavy and needs considerable work to get him in shape.” Baseball-Reference.com lists Eiteljorg at 6′ 2″ and 190 pounds. When he first pitched for the Cubs, the Chicago Inter Ocean listed his size as 5′ 10″ and 186. It also suggested that his ethnicity was Scandinavian (because of the J in his last name? The pronunciation?), even though Ed was born in Berlin. Calling Eiteljorg Scandianavian happened somewhat frequently over his early baseball career. As for his pitching technique, a later article in the Kansas City Times noted that, “He has a very rapid and very quick delivery and fields his position passably well.” He was a pretty fair athlete – he won a 100 yard dash while with Kansas City in 1892.

After easy wins over Pittsburgh in an early series, Cap Anson decided to give Eiteljorge a start against the Pirates on May 2, 1890. Eiteljorg got through the first inning without a scratch, but the second inning got out of hand pretty quickly. Pittsburgh scored five runs, with John Kelty’s triple being the big hit of the inning. When Eiteljorg gave up a single and a walk to open the third, Anson pulled Eiteljorg for a reliever. (By the way, Eiteljorg is given credit for having faced twelve batters on Baseball-Reference.com, but it’s actually 14 batters…)

Within days, Eiteljorg was sent out for more professional experience. The Colts farmed him out to Evansville of the Interstate League – which caused a little disturbance as some teams felt it was unfair for a player who signed a contract with a major league team to play for a minor league club. Eiteljorge pitched remarkably well for Evansville, winning 22 of 30 decisions, completing all 30 of his starts, and pitching in relief three other times.

As the season ended in the Interstate League, Eiteljorg didn’t return to the Colts. Rather, he signed with Omaha of the Western Association. Eiteljorg pitched well enough in a handful of starts to get a contract for the 1891 season. Along the way, Eiteljorg participated in a rare triple header on September 28, 1890 between Omaha and St. Paul. In the first game, Eiteljorg played centefrield and got a hit in a 7 – 5 Omaha win. In game two, he pitched a complete game (though sloppy), 15 – 7 win. He added a hit and a run to his batting totals in that game, too. Then, in game three, he had four hits including a home run – while starting the game in right field before taking the mound and earning the win relief of a game called by darkness with Omaha leading 16 – 11.

A couple of interesting stories about Eiteljorg can be found. In one of his first starts for Omaha, he was pitching in Minneapolis when the crowd called him “Idle George” and asked him if his mother knew he was out playing. The MIllers got out to an early lead, but Eiteljorg settled in. While his teammates rallied to take the lead (Ed himself had two hits), Eiteljorg fanned eight batters in the last five innings to earn the win.

An odder story of Eiterjorg’s playing days was told in 1922. According to lore, during a tie ball game with a runner at third base, Eiteljorg chose to give a pass to Jack Pickett. Pickett had a reputation as a hard hitter and with the winning run on third, Pickett worked the count such that Eiteljorg thought he had a better chance to pick him off first base than get Pickett out with a pitch. So, Pickett drew the walk. Eiteljorg had a good move to first, but not good enough this game and Pickett realized he was in Eiteljorg’s head. So, he started yelling things at Eiteljorg and eventually walked toward him as if to fight. Eiteljorg left the mound toward Pickett – and at some point, he calmly tagged Pickett out.

Pickett started laughing. The catcher had been yelling, “Throw the ball home!” With Eiteljorg not paying attention, the runner at third started running and easily scored the winning run.

(I have looked through the papers from 1890 to 1892 when this game could have happened and haven’t found an article to confirm it happened as described more than three decades later.)

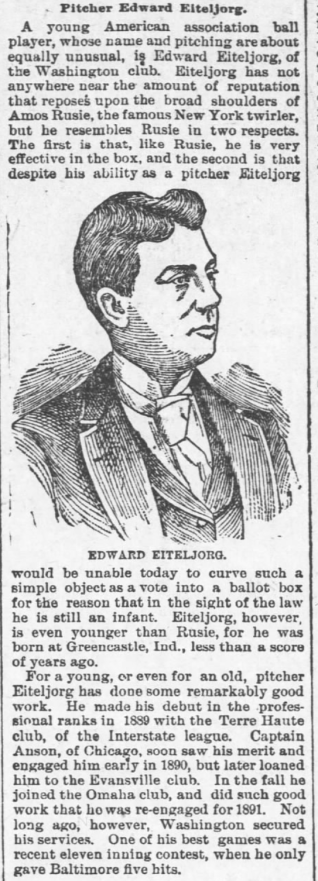

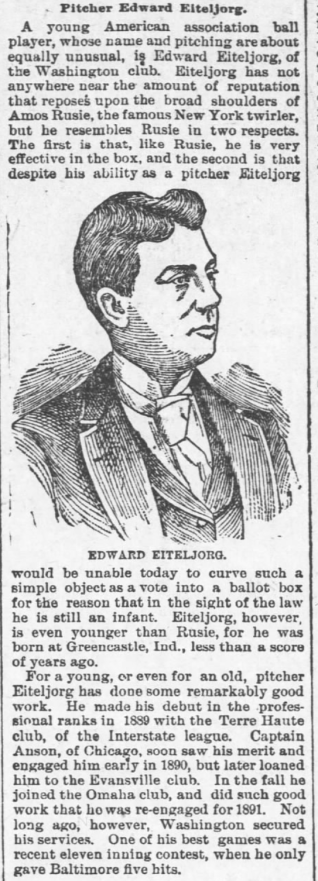

Eiteljorg pitched well for Omaha, however, winning 18 of 26 decisions with an excellent 1.68 ERA. However, the team disbanded in July. As Washington was near the bottom of the American Association standings, they signed the young prospect for the remainder of the 1891 season.

Here, the husky right hander struggled on a poor team. He won just once, losing five other decisions, in his eight appearances (seven starts) with Washington. His 6.16 ERA was bad enough, but he allowed 67 runs in his 61.1 innings and he walked nearly twice as many batters as he struck out. Eiteljorg’s explanation for his poor pitching was that he was immediately discouraged by watching Washington lose. “I was there a week before I went in the box and a week’s watching of the kind of baseball the ‘senators’ played was enough for me. It was something awful. They gave a pitcher no support at all. When I went into the box I had no heart, knew I couldn’t win and, as a rule, I didn’t.”

He did have one successful start, however. On August 22, 1891, he beat Baltimore in eleven innings, 3 – 2. In that game, he allowed but 5 hits though he walked seven. Unfortunately, only 648 fans witnessed the game that gave Eiteljorg his lone major league victory.

Omaha reorganized for the 1892 season and demanded that all of their players return to Omaha for that season. Eiteljorg was one of many players who refused to go to Omaha and, at least for a short period of time, he was blacklisted. At some point, his ability to play was restored and he landed with Kansas City in the Western League for 1892. When the locals first met Eiteljorg, he made a wonderful impression.

“Eddie Eiteljorg, the young man who is expected to be Kansas City’s mainstay in the box, is perhaps the nicest looking ball player who steps on a Western League diamond… He is a tall well-formed fellow and looks rather young. He has great speed and is the master of an excellent set of curves… It is pleasant to hear that he thinks Kansas City is the best town in the Western League, and that he would rather play here than in any of the western cities.”

Kansas City Times, April 1, 1892: 2. (The title of the article is obscured by age.)

Here, Eiteljorg was good but not good enough on a poor team, finishing with a 7-13 record in 21 starts and one relief appearance, despite a 2.33 ERA. Most of his problems were tied to his wildness. In one start against Toledo, for example, he walked a dozen batters. A few weeks later, the Kansas City Star said of Eiteljorg, “Eiteljorg was as erratic in his delivery as usual, and when he did get the balls over the plate, the Toledos rapped him hard… Eiteljorg was expected to be the star pitcher of the Blues, but his work has been very disappointing of late, and a little lay off without pay would probably have a good effect in putting into pitching form.” In that game, he walked eleven batters and served up two homers. At that point, Eiteljorg was moved to left field. “And, by the way, that’s where Eiteljorg ought to play whenever it is convenient,” wrote the Kansas City Times. “The way he used his bat yesterday showed what a desirable man he is to have about. He made a two bagger and a home run. His home run hit was a terrific drive over the left field fence between left and center field. He made two other long drives which were caught. It certainly cannot hurt the outfield to let Eiteljorg play there, for, as consituted now, Kansas City has the worst outfield on the face of the earth, bar none. (Art) Sunday alone plays the game.”

For what it’s worth, Eiteljorg tied for the team lead in home runs with three on the season (he batted .243 with the fourth highest slugging percentage on the team), and his control got better in the final weeks of the season. He even pitched a four-hit shutout to beat Omaha in June. However, Kansas City folded in July and Eiteljorg didn’t sign with another team for the season. For the near future, Eiteljorg’s pitching would be in lower level minor league or amateur teams.

The summer of 1893 saw Eiteljorg pitching with Muncie in the Indiana-Illinois League, despite rumors of his signing to pitch in the south or the east. However, for the most part Eiteljorg would spend much of 1893 and 1894 playing some amateur baseball and working a family farm.

In 1895, Eiteljorg started the season playing for Terre Haute – either pitching or playing in the outfield. By mid-summer, he was pitching for an amateur team in the small town of Kansas, Illinois – which happens to be about the same distance west of Terre Haute, IN as Greencastle, IN is east of Terre Haute. “Eiteljorg… has had a little League experience, but at the time he was tried out by the major organization was a raw, green, undeveloped boy. Since then he has developed into a splendid specimen of the strong, trim, clean-built athlete. Under the tutelage of an intelligent manager he would undoubtably blossom into a fine pitcher.” That Kansas team went undefeated with Eiteljorg pitching in every game, leading to a brief resurgence of his professional career.

Eiteljorg was picked up by Grand Rapids of the Western League. He didn’t impress in his first start, a loss to Columbus where Eiteljorg was removed in the third inning, leading to comments that he wouldn’t last the season in the Western League. Part of the problem was erratic control. On a May 14, 1896 start against Minneapolis, Eiteljorg walked a dozen batters – even though the game was called in the seventh inning because of rain. When not on the mound, he would play right field as needed. By late May, his arm was bothering him; by late June, predictions of Eiteljorg’s demise were correct. He was released and signed to pitch for Terre Haute in the Indiana-Illinois League. He would pitch there on and off between 1896 and 1899. With that, his days as a professional would end – he would pitch or play in amateur games and make a living as a farmer.

Starting in 1902, Eiteljorg – who had umpired games as early as his late teens in local events – started umpiring collegiate baseball. He’s seen behind the plate for games between many of the Indiana based universities, including Notre Dame, Purdue, Indiana, and his hometown DePauw. He had to take a brief break in 1903, however, when Purdue hired him as an assistant coach to help turn around a losing streak.

On August 9, 1893, Ed married Virginia Richmond Hammond. Living and working on a local farm, he and Virginia would have three children: Charlotte, Charles, and Edward. For some period of time around the turn of the century he also worked as a salesman at a local store.

Somewhere after his baseball days were over, Eiteljorg became Eiteljorge. And, Ed Eiteljorge became more active in civic matters. He served as a Greencastle township trustee and secretary of the library board. More importantly, he served as a deputy and later the sheriff of Putnam County for a handful of years. In one story, his wife Virginia heard the scratching of a key along the floor, catching a prisoner trying to use an improvised hook to steal the jail key – requiring that her husband find a new location to hang the extra key.

Somewhere after his baseball days were over, Eiteljorg became Eiteljorge. And, Ed Eiteljorge became more active in civic matters. He served as a Greencastle township trustee and secretary of the library board. More importantly, he served as a deputy and later the sheriff of Putnam County for a handful of years. In one story, his wife Virginia heard the scratching of a key along the floor, catching a prisoner trying to use an improvised hook to steal the jail key – requiring that her husband find a new location to hang the extra key.

Late in 1942 Eiteljorge began showing signs of decline due to arteriosclerosis. On December 5, he suffered a cerebral hemorrhage; he passed to the next league that afternoon. He is buried in Forest Hill Cemetery in Greencastle next to his wife, Virginia, who preceded him in death in 1936.

NOTES:

1880, 1900, 1910, 1930, 1940 US Census

Ellis Island Arrivals and Crew Lists

Indiana Death Certificates (Edward, Augusta)

Indiana Marriage Index

https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/e/eiteled01.shtml

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/26084038/edward-henry-eiteljorge

https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=1061837964409761 (Video shows the Terre Haute team image with names of players.)

https://www.ebay.com/itm/185026498574 (1889 Terre Haute team image on EBay)

“In the World of Sport,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, June 30, 1889: 2.

“A Coming Young Pitcher,” Indianapolis News, October 17, 1889: 2.

“Indian Summer Sports,” Buffalo Commercial Advertiser, October 21, 1889: 3.

“Eiteljorg Reports,” Chicago Tribune, April 3, 1890: 6.

“Hecker Slightly Happy,” Chicago Inter Ocean, May 3, 1890: 3.

“Won the Last of the Series,” Chicago Tribune, May 3, 1890: 6.

“The Quincys Downed,” Evansville Courier, May 14, 1890: 4.

“Fell From Grace,” Minneapolis Daily Times, September 6, 1890: 1.

“Omaha, 7-15-16; St. Paul, 5-7-11,” Sioux City Journal, September 29, 1890: 2.

“Athletics Were Pie for Washington,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 29, 1891: 3.

“Made It Three Straight,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 23, 1891: 3.

“Pitcher Edward Eiteljorg,” Topeka Capital, September 24, 1891: 3.

“Will Not Take Chances,” Boston Globe, January 24, 1892: 16.

“Composition of the Teams,” Kansas City Times, March 18, 1892: 5.

Kansas City Times, April 1, 1892: 2.

“Warm Welcome For Pears,” Kansas City Times, April 28, 1892: 2.

“A Game in Rain and Mud,” Kansas City Star, May 14, 1892: 3.

“Won By Very Hard Hitting,” Kansas City Times, May 27, 1892: 2.

“Two Games From Omaha,” Kansas City Times, June 4, 1892: 2.

“Eiteljorg The Fastest Man,” Kansas City Times, July 18, 1892: 3.

“The Blues Scattering,” Kansas City Star, July 25, 1892: 3.

“Retrieved,” Muncie Morning News, June 21, 1893: 8.

“The Pitcher Was Amusing,” Indianapolis Journal, April 13, 1895: 3.

“A Tip for Diddlebock,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 19, 1896: 5.

“Baseball,” Muncie Evening Press, April 23, 1896: 3.

“Baseball Notes,” Indianapolis Journal, April 24, 1896: 3.

“A Pitcher Squelched,” Indianapolis Journal, April 26, 1896: 3.

“Too Soft to Miss,” St. Paul Globe, May 15, 1896: 6.

“Blues Batted Out Victory,” Kansas City Times, May 24, 1896: 3.

“An Error Saved Shut-Out for Muncie,” Indianapolis Journal, June 23, 1899: 6.

“Could Not Stop Them, Indianapolis Journal, May 3, 1902: 2.

“New Coach at Purdue,” Indianapolis Journal, May 23, 1903: 2.

“Aided by Errors, I. U. Defeated Purdue,” Indianapolis Journal, May 24, 1904: 8.

“Depauw Gets Game by Forfeit,” Chicago Tribune, June 7, 1904: 8.

E. J. Bartley, “Baseball Freak Plays,” Pittsburgh Post, December 10, 1922: Section 3, Page 9.

“Prisoners Try to Hook Key,” Indianapolis Times, May 24, 1929: 36.

Photo of Eiteljorge – Indianapolis Star, June 11, 1929: 3.

“Rites Held for Mary Morgan,” Indianapolis News, October 10, 1936: 9.

“Legal Status of Board is Questioned,” The Daily Reporter (Martinsville, IN), March 19, 1937: 1.

Thomas Gilbert Vickery was a pitcher (and, according to articles, a puncher and kicker – earning the nickname “Vinegar Tom”) in the early 1890s. His first taste of the big leagues was with the Philadelphia NL club in 1890, getting a chance because so many players jumped to the Players League. (He had a good season at Toronto in 1889, which earned some consideration.) Knowing that the brotherhood might affect the National League teams’ ability to sign players, the owner of the Phillies, Al Reach, picked up a few players from minor league clubs, including Vickery and Jake Virtue.

Thomas Gilbert Vickery was a pitcher (and, according to articles, a puncher and kicker – earning the nickname “Vinegar Tom”) in the early 1890s. His first taste of the big leagues was with the Philadelphia NL club in 1890, getting a chance because so many players jumped to the Players League. (He had a good season at Toronto in 1889, which earned some consideration.) Knowing that the brotherhood might affect the National League teams’ ability to sign players, the owner of the Phillies, Al Reach, picked up a few players from minor league clubs, including Vickery and Jake Virtue.

Arthur Algernon Allison was born on

Arthur Algernon Allison was born on  Like some animals found at the Tulsa Zoo where he once worked, Tom Evanoff was a unique species. Evanoff was unusually intelligent, possessed of both left- and right-brained tendencies, and comfortable in structured and unstructured worlds. On January 5, 2024, Evanoff passed away due to complications associated with dementia in Murfreesboro, Tennessee. He was 81.

Like some animals found at the Tulsa Zoo where he once worked, Tom Evanoff was a unique species. Evanoff was unusually intelligent, possessed of both left- and right-brained tendencies, and comfortable in structured and unstructured worlds. On January 5, 2024, Evanoff passed away due to complications associated with dementia in Murfreesboro, Tennessee. He was 81. Ed Eiteljorg had just turned one year old when his family disembarked from their ship Main at Ellis Island in 1872. Soon after landing in the United States, the family settled in Indiana where Eiteljorg learned the ways of America, including the national pastime of baseball.

Ed Eiteljorg had just turned one year old when his family disembarked from their ship Main at Ellis Island in 1872. Soon after landing in the United States, the family settled in Indiana where Eiteljorg learned the ways of America, including the national pastime of baseball.

Somewhere after his baseball days were over, Eiteljorg became Eiteljorge. And, Ed Eiteljorge became more active in civic matters. He served as a Greencastle township trustee and secretary of the library board. More importantly, he served as a deputy and later the sheriff of Putnam County for a handful of years. In one story, his wife Virginia heard the scratching of a key along the floor, catching a prisoner trying to use an improvised hook to steal the jail key – requiring that her husband find a new location to hang the extra key.

Somewhere after his baseball days were over, Eiteljorg became Eiteljorge. And, Ed Eiteljorge became more active in civic matters. He served as a Greencastle township trustee and secretary of the library board. More importantly, he served as a deputy and later the sheriff of Putnam County for a handful of years. In one story, his wife Virginia heard the scratching of a key along the floor, catching a prisoner trying to use an improvised hook to steal the jail key – requiring that her husband find a new location to hang the extra key.